Some 12,000 years ago as the steely grip of the last ice age began to loosen and the vast ice sheets that covered Caledonia receded, Scotlands landscape underwent a massive and dramatic transformation.

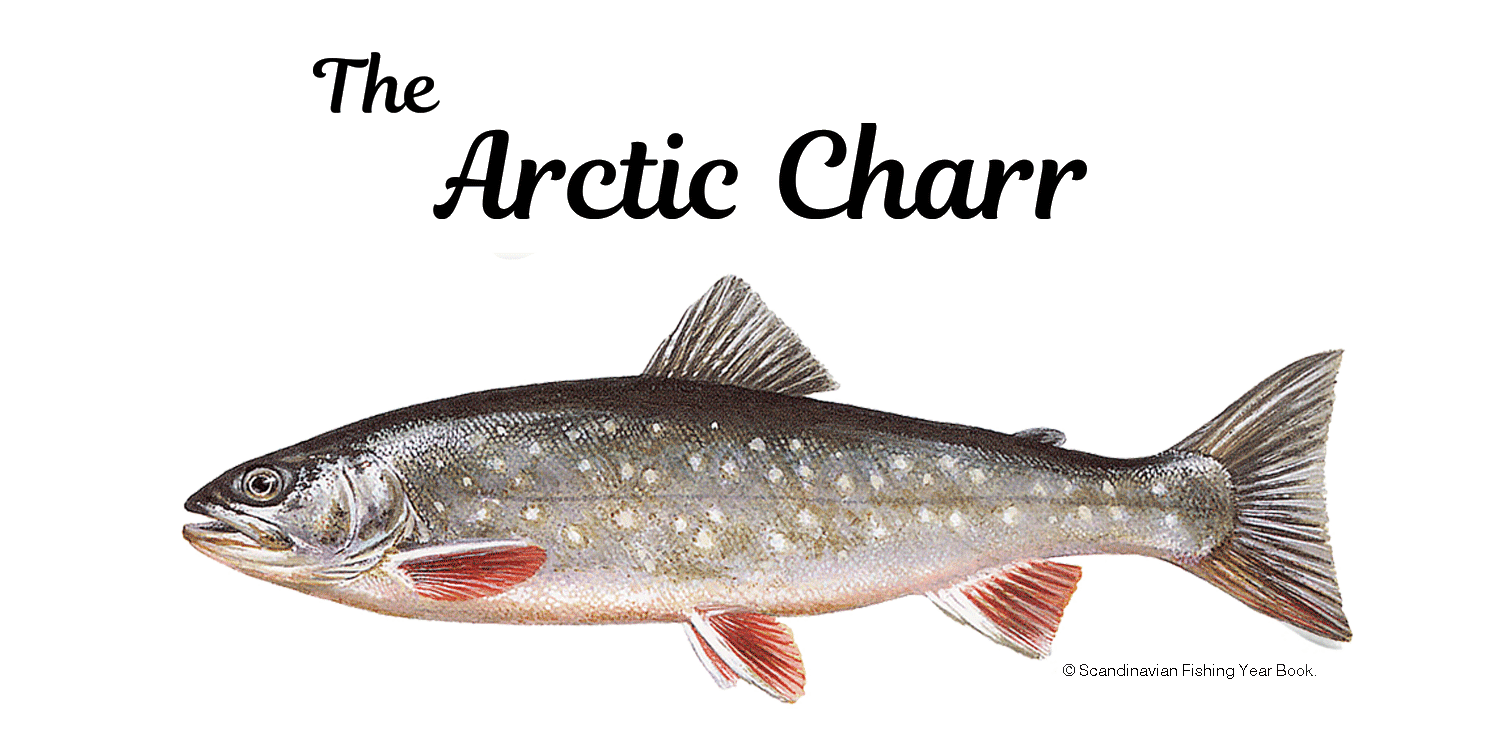

As the ice retreated, leaving in its wake deep water filled glens and rivers, one of the early arrivals was Salvelinus alpinus the Arctic Charr.

PIONEERS

These early pioneers were in many ways following in the footsteps of our present day sea trout who themselves ventured inland from their marine environment and subsequently remained to become todays freshwater loch resident brown trout.

The Arctic Charr, unlike their brown trout and sea trout cousins, are most often found in the deeper post glacial lochs and now find themselves entirely landlocked.

When you consider that these original freshwater invaders would have already shown considerable variation in appearance and behavioural characteristics then it is not surprising to find considerable diversification within the evolutionary gene pool of our now isolated freshwater populations.

Evidence has shown that although there are wide variations in the evolution of the brown trout, who themselves have undergone similar journeys, charr have shown an even greater diversification.

Today in our Scottish lochs the individual charr populations frequently show quite dramatic and profound differences in their growth, diet, colouration, shape and behaviour.

Given such diversification it is understandable that early biological studies led to the mistaken belief that there were as many as fifteen individual species in U.K. waters.

SPECIES

Nowadays it is generally accepted that collectively they are one species albeit with considerable diversity and variation within populations. That said the natural inclination for Arctic Charr, in certain circumstances, to exhibit quite dramatically differing variations is truly quite remarkable.

Examples of this diversity have been found in Loch Rannoch where evidence suggests as many as three differing strains of Arctic Charr.

A bottom dwelling “Benthivorous” form ~ with a lifespan of circa 11 years that shows rapid growth and a diet of bottom dwelling invertebrates. Regardless of the size sampled they were never found to have consumed fish with their stomach contents showing predominantly Pisidium (tiny pea mussel), midge larvae and water fleas.

An open water “Planktivorous” form ~ with a lifespan of circa 7 years which once again, similar to the Benthivorous form, shows rapid growth this time with a diet of mid-water dwelling invertebrates, mainly water flea and midge larvae.

Whilst both of the above show initial rapid growth their final size is limited with the Benthivorous form achieving a slightly greater final weight.

And finally a deep water “Piscivorous” form ~ with a predominantly fish eating diet and a currently unknown final size potential with one individual of over 17 years of age weighing in at 5.5 lbs.

Interestingly the Piscivorous strain actually begin their lives as Benthivorous before switching to a fish diet upon reaching roughly 16 cms.

Another most notable feature is that female Piscivorous charr have been found both ripe and sexually mature when smaller than 7.5 cms. in length.

Further evidence of the differences between individual strains in Rannoch can be found when spawning behaviour is taken into consideration.

The Benthivorous strain spawn in the mouth of the River Gaur, the major tributary which enters Loch Rannoch from the west, whilst the Planktivorous strain choose relatively shallow areas of gravelly wave washed shoreline with Piscivores showing a similar preference but for deeper water.

With these Rannoch charr originating from the same gene pool yet showing clear early individual behavioural differences, diet, habitat and spawning, shows such characteristics are determined by environmental influences rather that genetics.