APPEARANCE

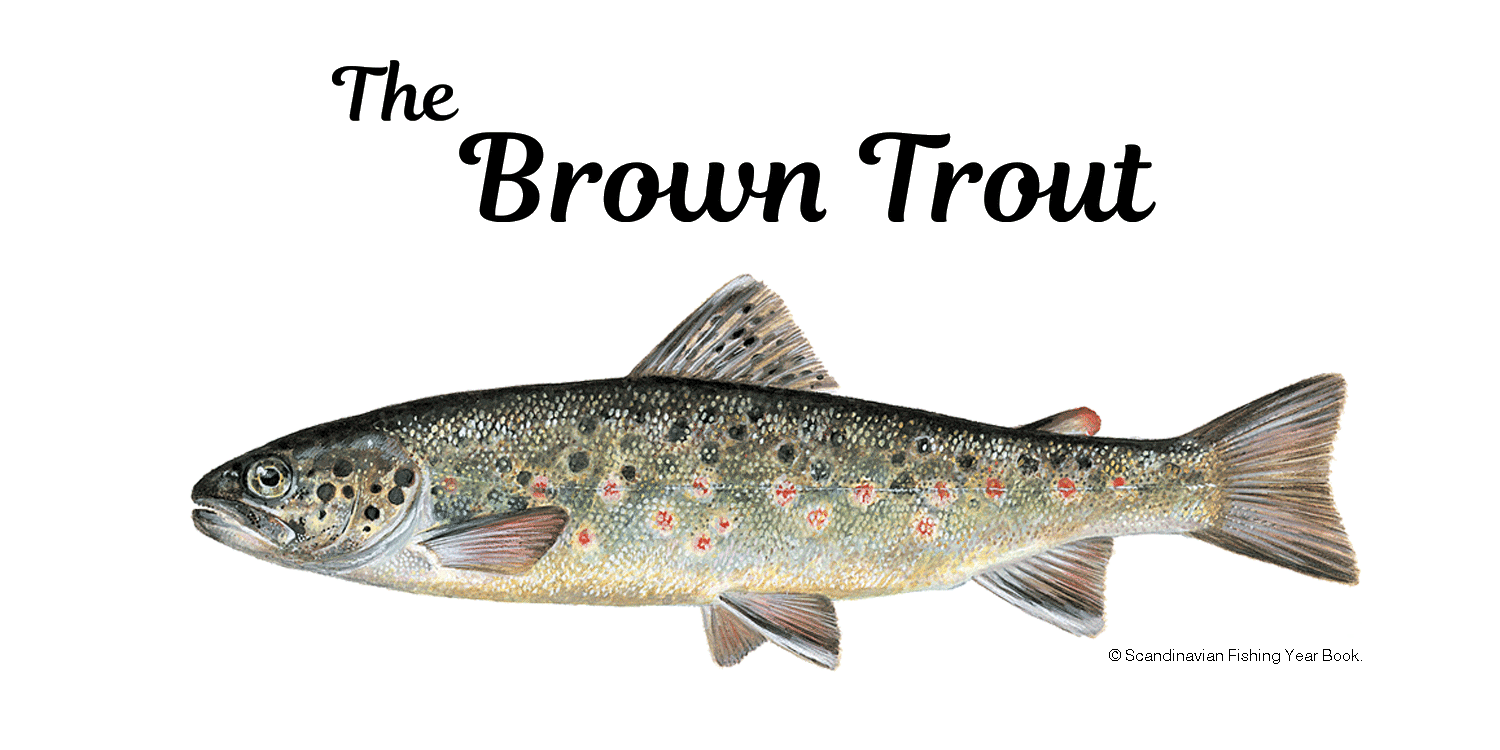

For such an often strikingly beautiful fish, given the vast diversity of both pattern and colouration, it seems strange for it to have been named rather modestly as simply a Brown Trout.

CHROMOTOPHORE

Whilst Brown Trout generally have dark brown backs, lighter flanks often bejewelled with black and/or red spots, pale bellies and dark reddish brown fins they also possess the ability to change their appearance by rearranging the pigment distribution of their chromatophoric skin cells.

This inherent genetic ability allows them to alter their appearance and blend in with their surrounding environs and thus help avoid both detection and predation. Brown Trout are also capable of becoming darker when aggressive and lighter when submissive.

These colour changing chromotophore cells can also be found in amphibians, reptiles, crustaceans and cephalopods such as octopus, squid and cuttlefish. This appearance altering ability goes some way to explain the diverse colouration and markings we find in our native Brown Trout.

These variations can range from the dull dark stunted trout lurking in the shadows of a low nutrient acidic highland lochan to the magnificent deep golden bronze yellow bellied specimens with their sides bedecked with black, red and sometimes even blue spots to be found in waters with better feeding. With all this diversity it's perhaps easier to understand the earlier held mistaken belief that we were in fact dealing with differing species.

SEA TROUT

It's worth reminding ourselves at this point that our Brown Trout and the anadromous Sea Trout are in fact genetically exactly the same species with the latter taking the decision, for a variety of reasons, to make the journey to sea where they grow large on a much richer marine diet.

Also, with them being the same species, it will come as no surprise that they can interbreed without issue.

SLOB TROUT

Yet another behavioural variation is the Brown Trout that - whilst not migrating to a fully marine environment like the Sea Trout – is content to move back and forth between the tides and feed in both freshwater and estuary, these trout are known rather unkindly I might suggest as “slob” trout.

Once thought - yet again - to be an entirely different species, the Slob Trout due to its physiology is capable of thriving in the brackish estuarial environment however unlike the Sea Trout does not go through the smoltification process.

These superbly proportioned Slob Trout ~ fuelled by the highly nutritious feeding in the estuary where shrimp, sand eel and small fish can be found in abundance ~ are an incredible sport fish often reach considerable size with three to four pound trout and beyond not uncommon.

FEROX

For some considerable time there were heated exchanges between contradicting held scientific viewpoints regarding whether Brown Trout “Salmo Trutta” and Ferox Trout “Salmo Ferox” were an entirely different species or whether the latter were simply Brown Trout that had grown large having switched to a predominantly fish diet.

We have now come to accept that the Brown Trout and the Ferox Trout, whilst having distinctly different appearance, diet, growth, habitat and behaviour do in fact belong to the same classification of Salmo Trutta and are therefore the same species.

GENETICS

Our Brown Trout, or “broonies” as they are affectionately known, have one of the greatest levels of genetic variation seen in any invertebrate with trout having between 38 and 42 pairs of chromosomes.

When you consider humans have only 23 pairs this equates to there being more diverse genetic variations in our wild Brown Trout than there are in the entire human race.

More to follow shortly ;o)